Callbacks in JavaScript

Have you come across the term “callback” but don’t know what it means? Don’t worry, you’re not alone. Many newcomers to JavaScript find callbacks hard to understand too.

Although callbacks can be confusing, you still need to learn them thoroughly as they form a critical concept in JavaScript. You can’t get very far without knowing callbacks 🙁.

That’s what today’s article is for! You’ll learn what callbacks are, why they’re important, and how to use them. 😄

(Note: You’ll see ES6 arrow functions in this article. If you’re unfamiliar with them, I suggest checking out this ES6 post before continuing. (Just read the arrow functions part)).

What are callbacks?

A callback is a function that is passed into another function as an argument to be executed later. (Developers say you “call” a function when you execute a function, which is why callbacks are named callbacks).

They’re so common in JavaScript that you probably used callbacks yourself without knowing they’re called callbacks.

One example of a function that accepts a callback is addEventListener:

const button = document.querySelector('button')button.addEventListener('click', function (e) { // Adds clicked class to button this.classList.add('clicked')})Don’t see why this is a callback? What about this then?

const button = document.querySelector('button')

// Function that adds 'clicked' class to the elementfunction clicked(e) { this.classList.add('clicked')}

// Adds click function as a callback to the event listenerbutton.addEventListener('click', clicked)Here, we told JavaScript to listen for the click event on a button. If a click is detected, JavaScript should fire the clicked function. So, in this case, clicked is the callback while addEventListener is a function that accepts a callback.

See what a callback is now? :)

Let’s go through another example. This time, let’s say you wanted to filter an array of numbers to get a list that’s less than five. Here, you pass a callback into the filter function:

const numbers = [3, 4, 10, 20]const lesserThanFive = numbers.filter(num => num < 5)Now, if you do the above code with named functions, filtering the array would look like this instead:

const numbers = [3, 4, 10, 20]const getLessThanFive = num => num < 5

// Passing getLessThanFive function into filterconst lesserThanFive = numbers.filter(getLessThanFive)In this case, getLessThanFive is the callback. Array.filter is a function that accepts a callback function.

See why now? Callbacks are everywhere once you know what they are!

The example below shows you how to write a callback function and a callback-accepting function:

// Create a function that accepts another function as an argumentconst callbackAcceptingFunction = fn => { // Calls the function with any required arguments return fn(1, 2, 3)}

// Callback gets arguments from the above callconst callback = (arg1, arg2, arg3) => { return arg1 + arg2 + arg3}

// Passing a callback into a callback accepting functionconst result = callbackAcceptingFunction(callback)console.log(result) // 6Notice that, when you pass a callback into another function, you only pass the reference to the function (without executing it, thus without the parenthesis ()).

const result = callbackAcceptingFunction(callback)You only invoke (call) the callback in the callbackAcceptingFunction. When you do so, you can pass any number of arguments that the callback may require:

const callbackAcceptingFunction = fn => { // Calls the callback with three args fn(1, 2, 3)}These arguments passed into callbacks by the callbackAcceptingFunction then makes their way through the callback:

// Callback gets arguments from callbackAcceptingFunctionconst callback = (arg1, arg2, arg3) => { return arg1 + arg2 + arg3}That’s the anatomy of a callback. Now, you know addEventListener contains an event argument. :)

// Now you know where this event object comes from! :)button.addEventListener('click', event => { event.preventDefault()})Phew! That’s the basic idea for callbacks! Just remember the keyword: passing a function into another function and you’ll recall the mechanics I mentioned above.

(Side note: This ability to pass functions around is a big thing. It’s so big that functions in JavaScript are considered higher order functions. Higher order functions are also a big thing in a programming paradigm called Functional Programming).

But that’s a topic for another day. Now, I’m sure you’re beginning to see what callbacks are and how they’re used. But why? Why do you need callbacks?

Why use callbacks?

Callbacks are used in two different ways — in synchronous functions and asynchronous functions.

Callbacks in synchronous functions

If your code executes in a top to bottom, left to right fashion, sequentially, and waiting until one code has finished before the next line begins, then your code is synchronous.

Let’s look at an example to make it easier to understand:

const addOne = n => n + 1addOne(1) // 2addOne(2) // 3addOne(3) // 4addOne(4) // 5In the example above, addOne(1) executes first. Once it’s done, addOne(2) begins to execute. Once addOne(2) is done, addOne(3) executes. This process goes on until the last line of code gets executed.

Callbacks are used in synchronous functions when you want a part of the code to be easily swapped with something else.

So, back in the Array.filter example above, although we filtered the array to contain numbers that are less than five, you could easily reuse Array.filter to obtain an array of numbers that are greater than ten:

const numbers = [3, 4, 10, 20]const getLessThanFive = num => num < 5const getMoreThanTen = num => num > 10

// Passing getLessThanFive function into filterconst lesserThanFive = numbers.filter(getLessThanFive)

// Passing getMoreThanTen function into filterconst moreThanTen = numbers.filter(getMoreThanTen)This is why you’d use callbacks in a synchronous function. Now, let’s move on and look at why we use callbacks in asynchronous functions.

Callbacks in asynchronous functions

Asynchronous here means that, if JavaScript needs to wait for something to complete, it will execute the rest of the tasks given to it while waiting.

An example of an asynchronous function is setTimeout. It takes in a callback function to execute at a later time:

// Calls the callback after 1 secondsetTimeout(callback, 1000)Let’s see how setTimeout works if you give JavaScript another task to complete:

const tenSecondsLater = _ = > console.log('10 seconds passed!')

setTimeout(tenSecondsLater, 10000)console.log('Start!')In the code above, JavaScript executes setTimeout. Then, it waits for ten second and logs “10 seconds passed!”.

Meanwhile, while waiting for setTimeout to complete in 10 seconds, JavaScript executes console.log("Start!").

So, this is what you’ll see if you log the above code:

// What happens:// > Start! (almost immediately)// > 10 seconds passed! (after ten seconds)Ugh. Asynchronous operations sound complicated, aren’t they? But why do we use them everywhere in JavaScript?

To see why asynchronous operations are important, imagine JavaScript is a robot helper you have in your house. This helper is pretty dumb. It can only do one thing at a time. (This behavior is called single-threaded).

Let’s say you tell the robot helper to order some pizza for you. But, the robot is so dumb, that after calling the pizza house, the robots sits at your front door and waits for the pizza to be delivered. It can’t do anything else in the meantime.

You can’t get it to iron clothes, mop the floor, or do anything while it’s waiting. You need to wait 20 minutes till the pizza arrives before it’s willing to do anything else…

(This behavior is called blocking. Other operations are blocked when you wait for something to complete).

const orderPizza = flavour => { callPizzaShop(`I want a ${flavour} pizza`) waits20minsForPizzaToCome() // Nothing else can happen here bringPizzaToYou()}

orderPizza('Hawaiian')

// These two only starts after orderPizza is completedmopFloor()ironClothes()Now, blocking operations are a bummer. 🙁.

Why?

Let’s put the dumb robot helper into the context of a browser. Imagine you tell it to change the color of a button when the button is clicked.

What would this dumb robot do?

It stares intently at the button, ignoring every other command that comes, until the button gets clicked. Meanwhile, the user can’t select anything else. See where it goes now? That’s why asynchronous programming is such a big thing in JavaScript.

But to really understand what’s happening during asynchronous operations, we need to bring in another thing – the event loop.

The event loop

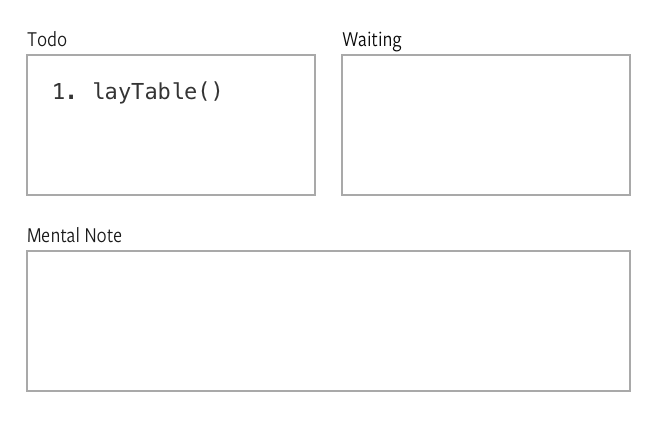

To envision the event loop, imagine JavaScript is a butler that carries around a todo-list. This list contains everything you told it to do. JavaScript will then go through the list, one by one, in the order you gave it.

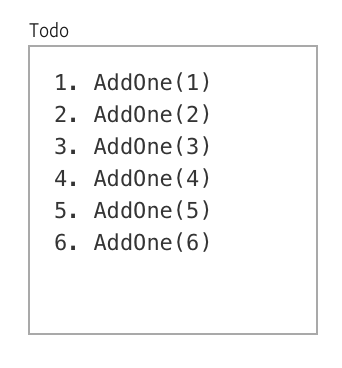

Let’s say you give JavaScript six commands as follows:

const addOne = n => n + 1

addOne(1) // 2addOne(2) // 3addOne(3) // 4addOne(4) // 5addOne(5) // 6addOne(6) // 7This is what would appear on JavaScript’s todo-list.

In addition to a todo-list, JavaScript also keeps a waiting-list where it tracks things it needs to wait for. If you tell JavaScript to order a pizza, it will call the pizza shop and adds “wait for pizza to arrive” in the waiting list. Meanwhile, it does other things that are already on the todo-list.

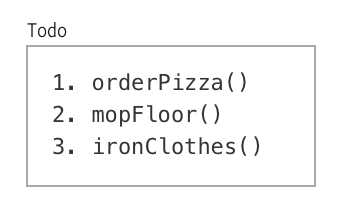

So, imagine you have this code:

const orderPizza (flavor, callback) { callPizzaShop(`I want a ${flavor} pizza`)

// Note: these three lines is pseudo code, not actual JavaScript whenPizzaComesBack { callback() }}

const layTheTable = _ => console.log('laying the table')

orderPizza('Hawaiian', layTheTable)mopFloor()ironClothes()JavaScript’s initial todo-list would be:

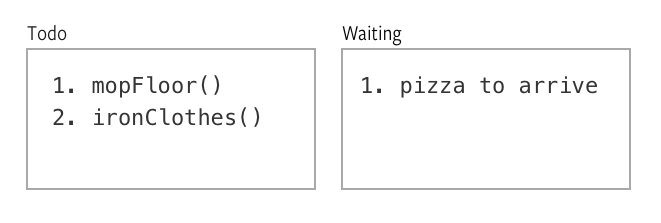

Then, while going through orderPizza, JavaScript knows it needs to wait for the pizza to arrive. So, it adds “waiting for pizza to arrive” to its waiting list while it tackles the rest of its jobs.

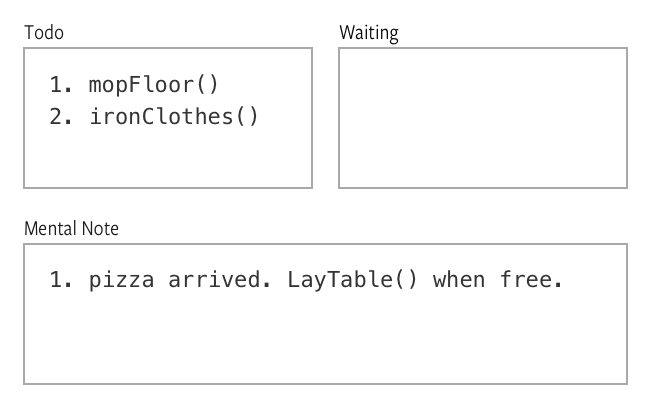

When the pizza arrives, JavaScript gets notified by the doorbell and it makes a mental note to execute layTheTable when it’s done with the other chores

Then, once it’s done with the other chores, JavaScript executes the callback function, layTheTable.

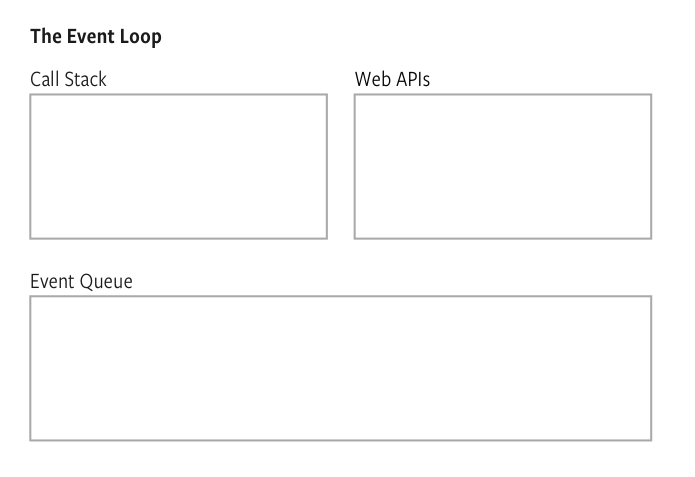

This, my friend, is called the Event Loop. You can substitute our butler analogy with actual keywords in the Event loop to understand everything:

- Todo-list -> Call stack

- Waiting-list -> Web apis

- Mental note -> Event queue

I highly recommend you watch Philip Roberts JSConf talk about event loops if you got 20 mins to spare. It’ll help you understand the nitty gritty of event loops.

Uhh… So, why are callbacks important again?

Ooh. We went a big round into event loops. Let’s come back 😂.

Previously, we mentioned that it would be bad if JavaScript stares intently at a button and ignores all other commands. Yes?

With asynchronous callbacks, we can give JavaScript instructions in advance without stopping the entire operation.

Now, when you ask JavaScript to watch a button for a click, it puts the “watch button” into the waiting-list and goes on with its chores. When the button finally gets a click, JavaScript activates the callback, then goes on with life.

Here are some common uses of callbacks to tell JavaScript what to do:

- When an event fires (like

addEventListener) - After AJAX calls (like

jQuery.ajax) - After reading or writing to files (like

fs.readFile)

// Callbacks in event listenersdocument.addEventListener(button, highlightTheButton)document.removeEventListener(button, highlightTheButton)

// Callbacks in jQuery's ajax method$.ajax('some-url', { success(data) { /* success callback */ }, error(err) { /* error callback */ },})

// Callbacks in Nodefs.readFile('pathToDirectory', (err, data) => { if (err) throw err console.log(data)})

// Callbacks in ExpressJSapp.get('/', (req, res) => res.sendFile(index.html))And that’s callbacks! 😄

Hopefully, you’re clear what callbacks are for and how to use them now. You won’t create a lot of callbacks yourself in the beginning, so focus on learning how to use the available ones.

Now, before we wrap up, let’s look at the #1 problem developers have with callbacks: callback hell.

Callback hell

Callback hell is a phenomenon where multiple callbacks are nested after each other. It can happen when you do an asynchronous activity that’s dependent on a previous asynchronous activity. These nested callbacks make code much harder to read.

In my experience, you’ll only see callback hell in Node. You’ll almost never encounter callback hell when working in on frontend JavaScript.

Here’s an example of callback hell:

// Look at three layers of callback in this code!app.get('/', function (req, res) { Users.findOne({ _id: req.body.id }, function (err, user) { if (user) { user.update( { /* params to update */ }, function (err, document) { res.json({ user: document }) }, ) } else { user.create(req.body, function (err, document) { res.json({ user: document }) }) } })})And now, a challenge for you: try to decipher the code above at a glance. Pretty hard, isn’t it? No wonder developers shudder at the sight of nested callbacks.

One solution to overcome callback hell is to break the callback functions into smaller pieces to reduce the amount of nested code:

const updateUser = (req, res) => { user.update( { /* params to update */ }, function () { if (err) throw err return res.json(user) }, )}

const createUser = (req, res, err, user) => { user.create(req.body, function (err, user) { res.json(user) })}

app.get('/', function (req, res) { Users.findOne({ _id: req.body.id }, (err, user) => { if (err) throw err if (user) { updateUser(req, res) } else { createUser(req, res) } })})Much easier to read, isn’t it?

There are other solutions to combat callback hell in newer versions of JavaScript like promises and async/await. But well, explaining them would be a topic for another day too.

Wrapping up

Today, you learned what callbacks are, why they’re so important in JavaScript and how to use them. You also learned about callback hell and a way to combat against it. Hopefully, callbacks no longer scare you now 😉.

Do you still have any questions about callbacks? Feel free to leave a comment down below if you do and I’ll get back to you as soon as I can.