Introduction to commonly used ES6 features

JavaScript has progressed a ton in the recent years. If you’re learning JavaScript in 2017 and you haven’t touched ES6, you’re missing out on an easier way to read and write JavaScript.

Don’t worry if you’re not a master at JavaScript yet. You don’t need to be awesome at JavaScript to take advantage of the added bonuses ES6 gives you. In this article, I want to share with you eight ES6 features I use daily as a developer to help you ease into the new syntax.

A list of ES6 features

First off, ES6 is a huge update to JavaScript. Here’s a big list of features if you’re curious about what’s new, thanks to Luke Hoban:

- Arrows

- Classes

- Enhanced object literals

- Template strings

- Destructuring

- Default + rest + spread

- Let + const

- Iterators + for..of

- Generators

- Unicode

- Modules

- Module loaders

- Map + set + weakmap + weakset

- Proxies

- Symbols

- Subclassable built-ins

- Promises

- Math + number + string + array + object apis

- Binary and octal literals

- Reflect api

- Tail calls

Don’t let this big list of features scare you away from ES6. You don’t need to know everything right away. I’m going to share with you eight of these features that I use on a daily basis. They are:

- Let and const

- Arrow functions

- Default parameters

- Destructuring

- Rest parameter and spread operator

- Enhanced object literals

- Template literals

- Promises

We’ll go through the eight features in the follow sections. For now, I’ll go through the first five features. I’ll add the rest as I go along in the next couple of weeks.

By the way, browser support for ES6 is amazing. Almost everything is supported natively if you code for the latest browsers (Edge, and latest versions of FF, Chrome and Safari).

You don’t need fancy tooling like Webpack if you wanted to write ES6. If browser support is lacking in your case, you can always fall back on polyfills created by the community. Just google them :)

With that, let’s jump into the first feature.

Let and const

In ES5 (the old JavaScript), we’re used to declaring variables with the var keyword. In ES6, this var keyword can be replaced by let and const, two powerful keywords that make developing simpler.

Let’s first look at the difference between let and var to understand why let and const are better.

Let vs var

Let’s talk about var first since we’re familiar with it.

First of all, we can declare variables with the var keyword. Once declared, this variable can be used anywhere in the current scope.

var me = 'Zell'console.log(me) // ZellIn the example above, I’ve declared me as a global variable. This global me variable can also be used in a function, like this:

var me = 'Zell'function sayMe() { console.log(me)}

sayMe() // ZellHowever, the reverse is not true. If I declare a variable in a function, I cannot use it outside the function.

function sayMe() { var me = 'Zell' console.log(me)}

sayMe() // Zellconsole.log(me) // Uncaught ReferenceError: me is not definedSo, we can say that var is function-scoped. This means whenever a variable is created with var in a function, it will only exist within the function.

If the variable is created outside of the function, it’ll exist in the outer scope.

var me = 'Zell' // global scope

function sayMe() { var me = 'Sleepy head' // local scope console.log(me)}

sayMe() // Sleepy headconsole.log(me) // Zelllet, on the other hand, is block-scoped. This means whenever a variable is created with let, it will only exist within its block.

But wait, what’s a block?

A block in JavaScript is anything within a pair of curly braces. The following are examples of blocks.

{ // new scope block}

if (true) { // new scope block}

while (true) { // new scope block}

function () { // new block scope}The difference between block-scope and function-scoped variables are huge. When you use a function-scoped variable, you may accidentally overwrite a variable without intending to do so. Here’s an example:

var me = 'Zell'

if (true) { var me = 'Sleepy head'}

console.log(me) // 'Sleepy head'In this example, you can see that me becomes Sleepy head after running through the if block. This example will likely not cause any problems for you since you probably won’t be declaring variables with the same name.

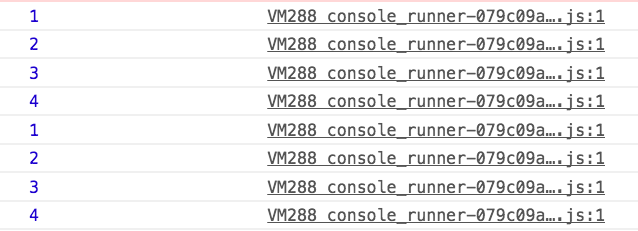

But anyone who works with var in a for loop situation may run into some weirdness because of the way variables are scoped. Consider the following code that logs the variable i four times, then logs i again with a setTimeout function.

for (var i = 1; i < 5; i++) { console.log(i) setTimeout(function () { console.log(i) }, 1000)}What would you expect this code to do? Here’s what actually happens

How the heck did i become 5 for four times inside the timeout function? Well, turns out, because var is function-scoped, the value of i became 4 even before the timeout function runs.

To get the correct i value within setTimeout, which executes later, we need to create another function, say logLater, to ensure the i value doesn’t get changed by the for loop before setTimeout executes:

function logLater(i) { setTimeout(function () { console.log(i) })}

for (var i = 1; i < 5; i++) { console.log(i) logLater(i)}

(By the way, this is called a closure).

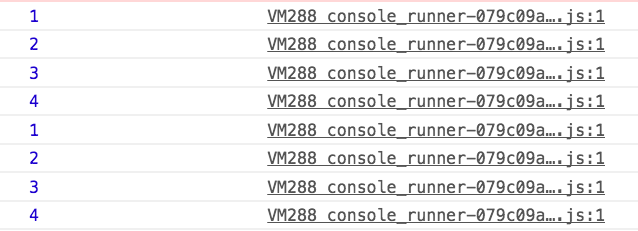

The good news is, function-scoped weirdness like the for loop example I’ve just shown you doesn’t happen with let. The same timeout example we’ve written earlier could be written as this, and it’ll work right out of the box without writing additional functions:

for (let i = 1; i < 5; i++) { console.log(i) setTimeout(function () { console.log(i) }, 1000)}

As you can see, block-scoped variables make development much simpler by removing common gotchas with function-scoped variables. To make life simple, I recommend you use let over var whenever you declare JavaScript variables from now on. (ES6 is the new JavaScript already 😎).

Now we know what let does, let’s move on to the difference between let and const.

Let vs const

Like let, const is also blocked-scoped. The difference is that const cannot be reassigned once declared.

const name = 'Zell'name = 'Sleepy head' // TypeError: Assignment to constant variable.

let name1 = 'Zell'name1 = 'Sleepy head'console.log(name1) // 'Sleepy head'Since const cannot be reassigned, they’re good for variables would not change.

Let’s say I have a button that launches a modal on my website. I know that there’s only going to be one button, and it wouldn’t change. In this case, I can use const.

const modalLauncher = document.querySelector('.jsModalLauncher')When declaring variables, I always prefer const over let whenever possible because I receive the extra cue that the variable would not get reassigned. Then, I use let for all other situations.

Next, let’s move on and talk about arrow functions.

Arrow Functions

Arrow functions are denoted by the fat arrow (=>) you see everywhere in ES6 code. It’s a shorthand to make anonymous functions. They can be used anywhere the function keyword is used. For example:

let array = [1, 7, 98, 5, 4, 2]

// ES5 wayvar moreThan20 = array.filter(function (num) { return num > 20})

// ES6 waylet moreThan20 = array.filter(num => num > 20)Arrow functions are pretty cool. They help make code shorter, which gives fewer room for errors to hide. They also help you write code that’s easier to understand once you get used to the syntax.

Let’s dive into the nitty-gritty of arrow functions so you learn to recognize and use them.

The nitty-gritty of arrow functions

First off, let’s talk about creating functions. In JavaScript, you’re probably used to creating functions this way:

function namedFunction() { // Do something}

// using the functionnamedFunction()There’s a second method to create functions. You can create an anonymous function and assign it to a variable. To create an anonymous function, we leave its name out of the function declaration.

var namedFunction = function () { // Do something}A third way to create functions is to create them directly as an argument to another function or method. This third use case is the most common one for anonymous functions. Here’s an example:

// Using an anonymous function in a callbackbutton.addEventListener('click', function () { // Do something})Since ES6 arrow functions are shorthand for anonymous functions, you can substitute arrow functions anywhere you create an anonymous function.

Here’s what it looks like:

// Normal Functionconst namedFunction = function (arg1, arg2) { /* do your stuff */}

// Arrow Functionconst namedFunction2 = (arg1, arg2) => { /* do your stuff */}

// Normal function in a callbackbutton.addEventListener('click', function () { // Do something})

// Arrow function in a callbackbutton.addEventListener('click', () => { // Do something})See the similarity here? Basically, you remove the function keyword and replace it with => at a slightly different location.

But what’s the big deal with arrow functions? Aren’t we just substituting function with =>?

Well, it turns out that we’re not just substituting function with =>. An arrow function’s syntax can change depending on two factors:

- The number of arguments required

- Whether you’d like an implicit return.

The first factor is the number of arguments supplied to the arrow function. If you only supply one argument, you can remove the parenthesis that surrounds the arguments. If no arguments are required, you can substitute the parenthesis (()) for an underscore (_).

All of the following are valid arrow functions.

const zeroArgs = () => {/* do something */}const zeroWithUnderscore = _ => {/* do something */}const oneArg = arg1 => {/* do something */}const oneArgWithParenthesis = (arg1) => {/* do something */}const manyArgs = (arg1, arg2) => {/* do something */}The second factor for arrow functions is whether you’d like an implicit return. Arrow functions, by default, automatically create a return keyword if the code only takes up one line, and is not enclosed in a block.

So, these two are equivalent:

const sum1 = (num1, num2) => num1 + num2const sum2 = (num1, num2) => { return num1 + num2}These two factors are the reason why you can write shorter code like the moreThan20 you’ve seen above:

let array = [1, 7, 98, 5, 4, 2]

// ES5 wayvar moreThan20 = array.filter(function (num) { return num > 20})

// ES6 waylet moreThan20 = array.filter(num => num > 20)In summary, arrow functions are pretty cool. They take a bit of time to get used to, so give it a try and you’ll be using it everywhere pretty soon.

But before you jump onto the arrow functions FTW bandwagon, I want to let you know about another nitty-gritty feature of the ES6 arrow function that cause a lot of confusion – the lexical this.

The lexical this

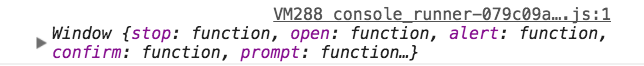

this is a unique keyword whose value changes depending on how it is called. When it’s called outside of any function, this defaults to the Window object in the browser.

console.log(this) // Window

When this is called in a simple function call, this is set to the global object. In the case of browsers, this will always be Window.

function hello() { console.log(this)}

hello() // WindowJavaScript always sets this to the window object within a simple function call. This explains why the this value within functions like setTimeout is always Window.

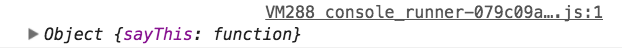

When this is called in an object method, this would be the object itself:

let o = { sayThis: function () { console.log(this) },}

o.sayThis() // o

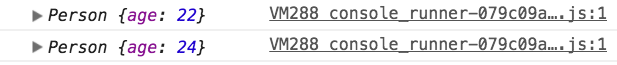

When the function is called as a constructor, this refers to the newly constructed object.

function Person(age) { this.age = age}

let greg = new Person(22)let thomas = new Person(24)

console.log(greg) // this.age = 22console.log(thomas) // this.age = 24

When used in an event listener, this is set to the element that fired the event.

let button = document.querySelector('button')

button.addEventListener('click', function () { console.log(this) // button})As you can see in the above situations, the value of this is set by the function that calls it. Every function defines it’s own this value.

In fat arrow functions, this never gets bound to a new value, no matter how the function is called. this will always be the same this value as its surrounding code. (By the way, lexical means relating to, which I guess, is how the lexical this got its name).

Okay, that sounds confusing, so let’s go through a few real examples.

First, you never want to use arrow functions to declare object methods, because you can’t reference the object with this anymore.

let o = { // Don't do this notThis: () => { console.log(this) // Window this.objectThis() // Uncaught TypeError: this.objectThis is not a function }, // Do this objectThis: function () { console.log(this) // o } // Or this, which is a new shorthand objectThis2 () { console.log(this) // o }}Second, you may not want to use arrow functions to create event listeners because this no longer binds to the element you attached your event listener to.

However, you can always get the right this context with event.currentTarget. Which is why I said may not.

button.addEventListener('click', function () { console.log(this) // button})

button.addEventListener('click', e => { console.log(this) // Window console.log(event.currentTarget) // button})Third, you may want to use the lexical this in places where the this binding changes without you wanting it to. An example is the timeout function, so you never have to deal with the this, that or self nonsense.

let o = { // Old way oldDoSthAfterThree: function () { let that = this setTimeout(function () { console.log(this) // Window console.log(that) // o }) }, // Arrow function way doSthAfterThree: function () { setTimeout(() => { console.log(this) // o }, 3000) },}This use case is particularly helpful if you needed to add or remove a class after some time has elapsed:

let o = { button: document.querySelector('button') endAnimation: function () { this.button.classList.add('is-closing') setTimeout(() => { this.button.classList.remove('is-closing') this.button.classList.remove('is-open') }, 3000) }}Finally, feel free to use the fat arrow function anywhere else to help make your code neater and shorter, like the moreThan20 example we had above:

let array = [1, 7, 98, 5, 4, 2]let moreThan20 = array.filter(num => num > 20)Let’s move on.

Default Parameters

Default parameters in ES6… well, gives us a way to specify default parameters when we define functions. Let’s go through an example and you’ll see how helpful it is.

Let’s say we’re creating a function that announces the name of a player from a team. If you write this function in ES5, it’ll be similar to the following:

function announcePlayer(firstName, lastName, teamName) { console.log(firstName + ' ' + lastName + ', ' + teamName)}

announcePlayer('Stephen', 'Curry', 'Golden State Warriors')// Stephen Curry, Golden State WarriorsAt first glance, this code looks ok. But what if we had to announce a player that’s unaffiliated with any team?

The current code fails embarrassingly if we left teamName out:

announcePlayer('Zell', 'Liew')// Zell Liew, undefinedI’m pretty sure undefined isn’t a team 😉.

If the player is unaffiliated, announcing Zell Liew, unaffiliated would make more sense that Zell Liew, undefined. Don’t you agree?

To get announcePlayer to announce Zell Liew, unaffiliated, we one way is to pass the unaffiliated string as the teamName:

announcePlayer('Zell', 'Liew', 'unaffiliated')// Zell Liew, unaffiliatedAlthough this works, we can do better by refactoring unaffiliated into announcePlayer by checking if teamName is defined.

In the ES5 version, you can refactor the code to something like this:

function announcePlayer(firstName, lastName, teamName) { if (!teamName) { teamName = 'unaffiliated' } console.log(firstName + ' ' + lastName + ', ' + teamName)}

announcePlayer('Zell', 'Liew')// Zell Liew, unaffiliated

announcePlayer('Stephen', 'Curry', 'Golden State Warriors')// Stephen Curry, Golden State WarriorsOr, if you’re savvier with ternary operators, you could have chosen a terser version:

function announcePlayer(firstName, lastName, teamName) { var team = teamName ? teamName : 'unaffiliated' console.log(firstName + ' ' + lastName + ', ' + team)}In ES6, with default parameters, we can add an equal sign (=) whenever we define a parameter. If we do so, ES6 automatically defaults to that value when the parameter is undefined.

So, in this code below, when teamName is undefined, it defaults to unaffiliated:

const announcePlayer = (firstName, lastName, teamName = 'unaffiliated') => { console.log(firstName + ' ' + lastName + ', ' + teamName)}

announcePlayer('Zell', 'Liew')// Zell Liew, unaffiliated

announcePlayer('Stephen', 'Curry', 'Golden State Warriors')// Stephen Curry, Golden State WarriorsPretty cool, isn’t it? :)

One more thing. If you want to invoke the default value, you can pass in undefined manually. This manual passing in of undefined helps when your default parameter isn’t the last argument of a function.

announcePlayer('Zell', 'Liew', undefined)// Zell Liew, unaffiliatedThat’s all you need to know about default parameters. It’s simple and very useful :)

Destructuring

Destructuring is a convenient way to get values out of arrays and objects. There are minor differences between destructuring array and objects, so let’s talk about them separately.

Destructuring objects

Let’s say you have the following object:

const Zell = { firstName: 'Zell', lastName: 'Liew',}To get the firstName and lastName from Zell, you had to create two variables, then assign each variable to a value, like this:

let firstName = Zell.firstName // Zelllet lastName = Zell.lastName // LiewWith destructuring, you can create and assign these variables with a single line of code. Here’s how you destructure objects:

let { firstName, lastName } = Zell

console.log(firstName) // Zellconsole.log(lastName) // LiewSee what happened here? By adding curly brackets ({}) while declaring variables, we’re telling JavaScript to create the aforementioned variables, then assign Zell.firstName to firstName and Zell.lastName to lastName respectively.

This is what’s going under the hood:

// What you writelet { firstName, lastName } = Zell

// ES6 does this automaticallylet firstName = Zell.firstNamelet lastName = Zell.lastNameNow, if a variable name is already used, we cannot declare the variable again (especially if you use let or const).

The following fails to work:

let name = 'Zell Liew'let course = { name: 'JS Fundamentals for Frontend Developers', // ... other properties}

let { name } = course // Uncaught SyntaxError: Identifier 'name' has already been declaredIf you run into situations like the above, you can rename variables while destructuring with a colon (:).

In this example below, I’m creating a courseName variable and assigning course.name to it.

let { name: courseName } = course

console.log(courseName) // JS Fundamentals for Frontend Developers

// What ES6 does under the hood:let courseName = course.nameOne more thing.

Don’t worry if you try to destructure a variable that’s not contained within an object. It will just return undefined.

let course = { name: 'JS Fundamentals for Frontend Developers',}

let { package } = course

console.log(package) // undefinedBut wait, that’s not all. Remember default parameters?

You can write default parameters for your destructured variables as well. The syntax is the same as that when you define functions.

let course = { name: 'JS Fundamentals for Frontend Developers',}

let { package = 'full course' } = course

console.log(package) // full courseYou can even rename variables while providing defaults. Just combine the two. It’ll look a little funny at the beginning, but you’ll get used to it if you use it often:

let course = { name: 'JS Fundamentals for Frontend Developers',}

let { package: packageName = 'full course' } = course

console.log(packageName) // full courseThat’s it for destructuring objects. Let’s move on and talk about destructuring arrays 😄.

Destructuring arrays

Destructuring arrays and destructuring objects are similar. We use square brackets ([]) instead of curly brackets ({}).

When you destructure an array,

- Your first variable is the first item in the array.

- Your second variable is the second item in the array.

- and so on…

let [one, two] = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]console.log(one) // 1console.log(two) // 2It is possible to destructure so many variables that you exceed the number of items in the given array. When this happens, the extra destructured variable will just be undefined.

let [one, two, three] = [1, 2]console.log(one) // 1console.log(two) // 2console.log(three) // undefinedWhen destructuring arrays, we often destructure only the variables we need. If you need the rest of the array, you can use the rest operator (...), like this:

let scores = ['98', '95', '93', '90', '87', '85']let [first, second, third, ...rest] = scores

console.log(first) // 98console.log(second) // 95console.log(third) // 93console.log(rest) // [90, 87, 85]We’ll talk more about rest operators in the following section. But for now, let’s talk about a unique ability you get with destructured arrays – swapping variables.

Swapping variables with destructured arrays

Let’s say you have two variables, a and b.

let a = 2let b = 3You wanted to swap these variables. So a = 3 and b = 2. In ES5, you need to use a temporary third variable to complete the swap:

let a = 2let b = 3let temp

// swappingtemp = a // temp is now 2a = b // a is now 3b = temp // b is now 2Although this works, the logic can be fuzzy and confusing, especially with the introduction of a third variable.

Now watch how you’ll do it the ES6 way with destructured arrays:

let a = 2let b = 3 // semicolon required because next line begins with a square bracket

// Swapping with destructured arrays;[a, b] = [b, a]

console.log(a) // 3console.log(b) // 2💥💥💥. So much simpler compared to the previous method of swapping variables! :)

Next, let’s talk about destructuring arrays and objects in a function.

Destructuring arrays and objects while declaring functions

The coolest thing about destructuring is that you can use them anywhere. Literally. You can even destructure objects and arrays in functions.

Let’s say we have a function that takes in an array of scores and returns an object with the top three scores. This function is similar to what we’ve done while destructuring arrays.

// Note: You don't need arrow functions to use any other ES6 featuresfunction topThree(scores) { let [first, second, third] = scores return { first: first, second: second, third: third, }}An alternate way to write this function is to destructure scores while declaring the function. In this case, there’s one less line of code to write. At the same time, we know we’re taking in an array.

function topThree([first, second, third]) { return { first: first, second: second, third: third, }}Super cool, isn’t it? 😄.

Now, here’s a quick little quiz for you. Since we can combine default parameters and destructuring while declaring functions, what does the following say?

function sayMyName({ firstName = 'Zell', lastName = 'Liew' } = {}) { console.log(firstName + ' ' + lastName)}This is a tricky one. We’re combining a few features together.

First, we can see that this function takes in one argument, an object. This object is optional and defaults to {} when undefined.

Second, we attempt to destructure firstName and lastName variables from the given object. If these properties are found, use them.

Finally, if firstName or lastName is undefined in the given object, we set it to Zell and Liew respectively.

So, this function produces the following results:

sayMyName() // Zell LiewsayMyName({ firstName: 'Zell' }) // Zell LiewsayMyName({ firstName: 'Vincy', lastName: 'Zhang' }) // Vincy ZhangPretty cool to combine destructuring and default parameters in a function declaration eh? 😄. I love this.

Next, let’s take a look at rest and spread.

The rest parameter and spread operator

The rest parameter and spread operator look the same. They’re both signified with three dots (...).

What they do is different depending on what they’re used for. That’s why they’re named differently. So, let’s take a look at the rest parameter and spread operator separately.

The rest parameter

Loosely translated, the rest parameter means take the rest of the stuff and pack it into an array. It converts a comma separated list of arguments into an array.

Let’s take a look at the rest parameter in action. Imagine we have a function, add, that sums up its arguments:

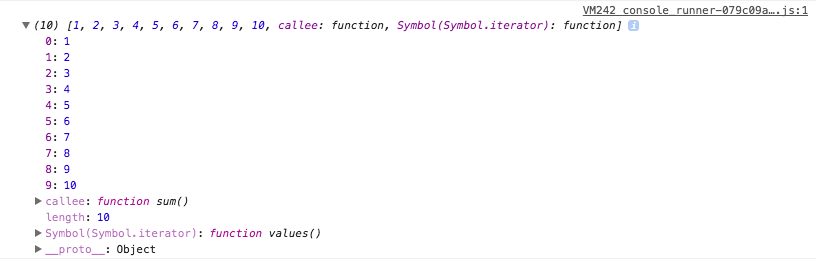

sum(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) // 55In ES5, we depended on the arguments variable whenever we had to deal with a function that takes in an unknown number of variables. This arguments variable is an array-like Symbol.

function sum() { console.log(arguments)}

sum(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10)

One way to calculate this sum of arguments is to convert it into an Array with Array.prototype.slice.call(arguments), then, loop through each number with an array method like forEach or reduce.

I’m sure you can do forEach on your own, so here’s the reduce example:

// ES5 wayfunction sum() { let argsArray = Array.prototype.slice.call(arguments) return argsArray.reduce(function (sum, current) { return sum + current }, 0)}With the ES6 rest parameter, we could pack all comma separated arguments straight into an array.

// ES6 wayconst sum = (...args) => args.reduce((sum, current) => sum + current, 0)

// ES6 way if we didn't shortcut it with so many arrow functionsfunction sum(...args) { return args.reduce((sum, current) => sum + current, 0)}Much cleaner? 🙂.

Now, we briefly encountered the rest parameter earlier in the destructuring section. There, we tried to destructure an array of scores into the top three scores:

let scores = ['98', '95', '93', '90', '87', '85']let [first, second, third] = scores

console.log(first) // 98console.log(second) // 95console.log(third) // 93If we wanted the rest of the scores, we could do so by packing the rest of the scores into an array with the rest parameter.

let scores = ['98', '95', '93', '90', '87', '85']let [first, second, third, ...restOfScores] = scores

console.log(restOfScores) // [90, 87, 85]If you’re ever confused, just remember this — the rest parameter packs everything into an array. It appears in function parameters and while destructuring arrays.

Next, let’s move on to spread.

The spread operator

The spread operator behaves in the opposite way compared to the rest parameter. Loosely put, it takes an array and spreads it (like jam) into a comma separated list of arguments.

let array = ['one', 'two', 'three']

// These two are exactly the sameconsole.log(...array) // one two threeconsole.log('one', 'two', 'three') // one two threeThe spread operator is often used to help concatenate arrays in a way that’s easier to read and understand.

Say for example, you wanted to concatenate the following arrays:

let array1 = ['one', 'two']let array2 = ['three', 'four']let array3 = ['five', 'six']The ES5 way of concatenating these two arrays is to use the Array.concat method. You can chain multiple Array.concat to concatenate any number of arrays, like this:

// ES5 waylet combinedArray = array1.concat(array2).concat(array3)console.log(combinedArray) // ['one', 'two', 'three', 'four', 'five', 'six']With ES6 spread operator, you could spread the arrays into a new array, like this, which is slightly easier to read once you get used to it:

// ES6 waylet combinedArray = [...array1, ...array2, ...array3]console.log(combinedArray) // ['one', 'two', 'three', 'four', 'five', 'six']The spread operator can also be used to remove an item from an array without mutating the array. This method is commonly used in Redux. I highly recommend you watch this video by Dan Abramov if you’re interested in seeing how it works out.

That’s it for spread :)

Enhanced object literals

Objects should be a familiar thing to you since you’re writing JavaScript. Just in case you don’t know about them, they look something like this:

const anObject = { property1: 'value1', property2: 'value2', property3: 'value3',}ES6 enhanced object literals brings three sweet upgrades to the objects you know and love. They are:

- Property value shorthands

- Method shorthands

- The ability to use computed property names

Let’s look at each one of them. I promise this will be quick :)

Property value shorthands

Have you noticed that you sometimes assign a variable that has the same name as an object property? You know, something like this:

const fullName = 'Zell Liew'

const Zell = { fullName: fullName,}Well, wouldn’t you wish you could write this in a shorter way, since the property (fullName) and value (fullName)?

(Oh you spoilt brat 😝).

Here’s the good news. You can! :)

ES6 enhances objects with property value shorthands. This means: you can write only the variable if your variable name matches your property name. ES6 takes care of the rest.

Here’s what it looks like:

const fullName = 'Zell Liew'

// ES6 wayconst Zell = { fullName,}

// Underneath the hood, ES6 does this:const Zell = { fullName: fullName,}Pretty neat, eh? Now, we have less words to write, and we all go home happy.

While I dance, please go on and move to more shorthand goodness. I’ll join you shortly.

Method shorthands

Methods are functions that are associated with a property. They’re just named specially because they’re functions :)

This is an example of a method:

const anObject = { aMethod: function () { console.log("I'm a method!~~") },}With ES6, we get to write methods with a shorthand. We can remove : function from a method declaration and it will work like it used to:

const anObject = { // ES6 way aShorthandMethod(arg1, arg2) {},

// ES5 way aLonghandMethod: function (arg1, arg2) {},}With this upgrade, objects already get a shorthand method, so please please don’t use arrow functions when you define objects. You’ll break the this context (see arrow functions if you can’t remember why).

const dontDoThis = { // Noooo. Don't do this arrowFunction: () => {},}That’s it with object method shorthands. Let’s move on to the final upgrade we get for objects.

Computed object property names

Sometimes you need a dynamic property name when you create objects. In the old JavaScript way, you’d have to create the object, then assign your property to in, like this:

// ES5const newPropertyName = 'smile'

// Create an object firstconst anObject = { aProperty: 'a value' }

// Then assign the propertyanObject[newPropertyName] = ':D'

// Adding a slightly different property and assigning itanObject['bigger ' + newPropertyName] = 'XD'

// Result// {// aProperty: 'a value',// 'bigger smile': 'XD'// smile: ':D',// }In ES6, you no longer need to do this roundabout way. You can assign dynamic property names directly when creating your object. The key is to enclose the dynamic property with square brackets:

const newPropertyName = 'smile'

// ES6 way.const anObject = { aProperty: 'a value', // Dynamic property names! [newPropertyName]: ':D', ['bigger ' + newPropertyName]: 'XD',}

// Result// {// aProperty: 'a value',// 'bigger smile': 'XD'// smile: ':D',// }Schweeet! Isn’t it? :)

And that’s it for enhanced object literals. Didn’t I say it’ll be quick? :)

Let’s move on to another awesome feature I absolutely love: template literals.

Template literals

Handling strings in JavaScript is an extremely clunky experience. You’ve experienced it yourself when we created the announcePlayer function previously in default parameters. There, we created spaces with empty strings and joined them with pluses:

function announcePlayer(firstName, lastName, teamName) { console.log(firstName + ' ' + lastName + ', ' + teamName)}In ES6, this problem goes away thanks to template literals! (In the specification, they were previously called template strings).

To create a template literal in ES6, you enclose strings with backticks (`). Within backticks, you gain access to a special placeholder (${}) where you can use JavaScript normally.

Here’s what it looks like in action:

const firstName = 'Zell'const lastName = 'Liew'const teamName = 'unaffiliated'

const theString = `${firstName} ${lastName}, ${teamName}`

console.log(theString)// Zell Liew, unaffiliatedSee that? We can group everything with template literals! Within template literals, it’s English as normal. Almost as if we’re using a template engine :)

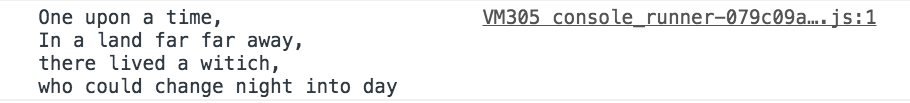

The best part about template literals is that you can create multi-line strings easily. This works out of the box:

const multi = `One upon a time,In a land far far away,there lived a witich,who could change night into day`

One neat trick is to use these strings to create HTML elements in JavaScript if you need them. (Note: This may not be best way to make HTML elements, but its still way better than creating them one by one!).

const container = document.createElement('div')const aListOfItems = `<ul> <li>Point number one</li> <li>Point number two</li> <li>Point number three</li> <li>Point number four</li> </ul>`

container.innerHTML = aListOfItems

document.body.append(container)Another feature of template literals is called tags. Tags are functions that allow you manipulate the template literal, if you wanted to substitute any string.

Here’s what it looks like:

const animal = 'lamb'

// This a tagconst tagFunction = () => { // Do something here}

// This tagFunction allows you to manipulate the template literal.const string = tagFunction`Mary had a little ${animal}`To be honest, even though template tags looks cool, I haven’t had a use case for them yet. If you want to learn more about template tags, I suggest you read this reference on MDN.

That’s it for template literals.

Wrapping up

Woo! That’s almost all the awesome ES6 features I use on a regular basis. ES6 is awesome. It’s definitely worth it to take a bit of your time and learn about them, so you can understand what everyone else is writing about.

Was this article helpful for you? Let me know in the comments below if you have any questions or thoughts! I’d love to hear them :)