Promises in JavaScript

Have you encountered promises in JavaScript and wondered what they are? Why are they called promises? Are they related to a promise you make to another person in any way?

Furthermore, why do you use promises? What benefits do they have over traditional callbacks for asynchronous JavaScript operations?

In this article, you’re going to learn all about JavaScript promises. You’ll understand what they are, how to use them and why they’re preferred over callbacks.

So, what is a promise?

A promise is an object that will return a value in future. Because of this “in future” thing, Promises are well suited for asynchronous JavaScript operations.

(If you’re unsure what asynchronous JavaScript means, you might not be ready for this article. I suggest you go through this article on callbacks first before coming back here).

The concept of a JavaScript promise is better explained through an analogy, so let’s do just that to help make the concept clearer.

Imagine you’re preparing for a birthday party for your niece next week. As you speak about the party, your friend, Jeff, offered to help. Delighted, you asked him to buy a black forest birthday cake. Jeff said okay.

Here, Jeff has given you his word that he’ll buy you a black forest birthday cake. It’s a promise. In JavaScript, a promise works the same way as a promise in real life. The JavaScript version of scenario can be written in the following way:

// jeffBuysCake is a promiseconst promise = jeffBuysCake('black forest')(You’ll learn how to construct jeffBuysCake later. For now, take it that its a promise).

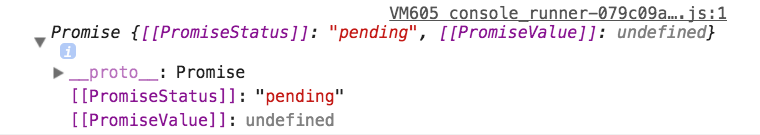

Right now, Jeff hasn’t acted on his promise yet. In JavaScript, we say the promise is pending. You can verify this if you console.log a promise object.

(When we construct jeffBuysCake together later, you will be able to verify this console.log statement for yourself).

You begin to plan your next steps after talking to Jeff. You realize that you can carry on the party as planned if Jeff keeps to his words and buys you a black forest cake in time for the party.

If Jeff does buy the cake, we say the promise is resolved in JavaScript. When a promise gets resolved, you do the next thing in a .then call:

jeffBuysCake('black forest') .then(partyAsPlanned) // Woohoo! 🎉🎉🎉But if Jeff doesn’t buy you the cake, you got to run to the bakery yourself. (Damn you, Jeff!). If this happens, we say the promise is rejected.

When a promise gets rejected, you do your contingency plan in a .catch call.

jeffBuysCake('black forest') .then(partyAsPlanned) .catch(buyCakeYourself) // Grumble Grumble... #*$%This, my friend, is an anatomy of a Promise.

In JavaScript, we usually use promises to get or modify a piece of information. When the promise resolves, we do something with the data that comes back. When the promise rejects, we handle the error:

getSomethingWithPromise() .then(data => {/* do something with data */}) .catch(err => {/* handle the error */})Now, you know how a promise works. Let’s dive in further and examine how to construct a promise.

Constructing a promise

You can make a promise by using new Promise. This Promise constructor takes in a function that contains two arguments — resolve and reject.

const promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => { /* Do something here */})If resolve is called, the promise succeeds and continues into the then chain. The parameter you pass into resolve would be the argument in the next then call:

const promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => { // Note: only 1 param allowed return resolve(27)})

// Parameter passed resolve would be the arguments passed into then.promise.then(number => console.log(number)) // 27If reject is called, the promise fails and continues into the catch chain. Likewise, the parameter you pass into reject would be the argument in the catch call.

const promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => { // Note: only 1 param allowed return reject('💩💩💩')})

// Parameter passed into reject would be the arguments passed into catch.promise.catch(err => console.log(err)) // 💩💩💩(Can you see that both resolve and reject are callbacks? 😉).

Let’s practice a little and try to construct jeffBuysCake promise.

First of all, you know that Jeff says he’ll buy a cake. That’s a promise. So, let’s begin with an empty promise:

const jeffBuysCake = cakeType => { return new Promise((resolve, reject) => { // Do something here })}Next, Jeff says he’s going to buy the cake in a week. Let’s use a setTimeout function to simulate this wait for seven days. Instead of seven days, we’ll wait for one second:

const jeffBuysCake = cakeType => { return new Promise((resolve, reject) => { setTimeout(()=> { // Checks if Jeff buys a black forest cake }, 1000) })}If Jeff bought a black forest cake after one second, we return the promise and pass the black forest cake into then.

If Jeff bought another type of cake, we reject the promise and say no cake, which causes the promise to go into catch.

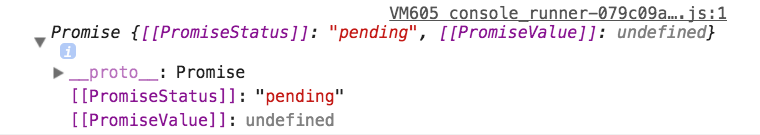

const jeffBuysCake = cakeType => { return new Promise((resolve, reject) => { setTimeout(()=> { if (cakeType === 'black forest') { resolve('black forest cake!') } else { reject('No cake 😢') } }, 1000) })}Let’s test this promise out. When you console.log the promise below, you should see that the promise is pending. (The status would only be pending if you checked the console immediately. Feel free to extend the timeout to ten seconds if you need more time to check the console).

const promise = jeffBuysCake('black forest')console.log(promise)

If you add then and catch into the promise chain, you’ll also see black forest cake! or no cake 😢 depending on the type of cake you passed into jeffBuysCake

const promise = jeffBuysCake('black forest') .then(cake => console.log(cake)) .catch(nocake => console.log(nocake))

Not too hard to make a promise, isn’t it? 😉.

Since you know what is a promise, how to make one and how to use one, let’s answer the next question — why use a promise instead of a callback for asynchronous JavaScript?

Promises vs. Callbacks

There are three reasons why developers prefer promises over callbacks:

- Promises reduces the amount of nested code

- Promises allow you to visualize the execution flow easily

- Promises let you handle all errors at once at the end of the chain.

To see these three benefits in action, let’s write some JavaScript code that does some asynchronous things with both callbacks and promises.

For this process, imagine you’re running an online shop. You need to charge a customer whenever he buys something, then, you enter their information into your database. Lastly, you’ll send them an email:

- Charge a customer

- Add customer to database

- Send email to customer

Let’s break in down step by step. First of all, you need a way to get information from your frontend to your backend. Normally, you’d use a post request for these operations.

If you use Express and Node, your initial code might look like the following. Don’t worry if you don’t know any Node or Express. They’re not the main part of the article. Just follow along:

// A little bit of NodeJS here. This is how you'll get data from the frontend through your API.app.post('/buy-thing', (req, res) => { const customer = req.body

// Charge customer here})Let’s go through the first step with callback-based code first. Here, you want to charge a customer. If this charge is successful, you add their information to a database. If the charge fails, you throw an error, so your server can handle the error.

The code looks like this:

// Callback based codeapp.post('/buy-thing', (req, res) => { const customer = req.body

// First operation: charge the customer chargeCustomer(customer, (err, charge) => { if (err) throw err

// Add to database here })})Now, let’s switch to promise-based code. Likewise, you charge a customer. If the charge is successful, you add their information to the database with a then call. If the charge fails, you handle it automatically within the catch call:

// Promised based codeapp.post('/buy-thing', (req, res) => { const customer = req.body

// First operation: charge the customer chargeCustomer(customer) .then(/* Add to database */) .catch(err => console.log(err))})Moving on, you add your customer information to your database when the charge succeeds. If your database operation succeeds, you send an email to your customer. Otherwise, you throw an error.

With these steps in mind, the callback-based code looks like this:

// Callback based codeapp.post('/buy-thing', (req, res) => { const customer = req.body

chargeCustomer(customer, (err, charge) => { if (err) throw err

// Second operation: Add to database addToDatabase(customer, (err, document) => { if (err) throw err

// Send email here }) })})For the promised-based code, if your database operation succeeds, you send the email in the next then call. If your database operation fails, the error automatically gets handled in the final catch statement:

// Promised based codeapp.post('/buy-thing', (req, res) => { const customer = req.body

chargeCustomer(customer) // Second operation: Add to database .then(_ => addToDatabase(customer)) .then(/* Send email */) .catch(err => console.log(err))})Moving on to the last step, you send an email to your customer when the database operation succeeds. If this emails is sent successfully, you notify your frontend with a success message. Otherwise, you throw an error:

Here’s how the callback-based code looks like:

app.post('/buy-thing', (req, res) => { const customer = req.body

chargeCustomer(customer, (err, charge) => { if (err) throw err

addToDatabase(customer, (err, document) => { if (err) throw err

sendEmail(customer, (err, result) => { if (err) throw err

// Tells frontend success message. res.send('success!') }) }) })})And here’s how the promise-based code looks like:

app.post('/buy-thing', (req, res) => { const customer = req.body

chargeCustomer(customer) .then(_ => addToDatabase(customer)) .then(_ => sendEmail(customer) ) .then(result => res.send('success!'))) .catch(err => console.log(err))})See why it’s much easier to write asynchronous code with promises instead of callbacks? You switch from callback hell into the happy-chain-land 😂.

Firing off multiple promises at once.

An additional benefit promises have over callbacks is that you can fire off two (or many) promises at the same time if the operations aren’t dependent on each other, but both results are needed to perform a third action.

To do so, you use the Promise.all method, then pass in an array of promises you’d like to wait for. Your then argument would then be an array that contains the results from your promises:

const friesPromise = getFries()const burgerPromise = getBurger()const drinksPromise = getDrinks()

const eatMeal = Promise.all([ friesPromise, burgerPromise, drinksPromise]) .then([fries, burger, drinks] => { console.log(`Chomp. Awesome ${burger}! 🍔`) console.log(`Chomp. Delicious ${fries}! 🍟`) console.log(`Slurp. Ugh, shitty drink ${drink} 🤢 `) })(Note: there’s also a method called Promise.race, but I haven’t found a proper use case for it. You can check it out here).

Finally, let’s talk about browser support! Why learn promises if you can’t use it in production. Right?

Browser support for Promise

The awesome news is: promises are supported in all major browsers!

If you need to support IE 11 and below, you can use Promise Polyfill by Taylor Hakes. It supports promises up to IE8! 😮.

Wrapping up

You learned all about promises in this article. In short, promises are rad. It helps you write asynchronous code without taking a step into callback hell.

Although you probably want to use promises whenever you can, there are cases where callbacks makes sense too. Don’t forget about callbacks 😉.

If you have a question, leave it in the comments below and I’ll get back to you as soon as I can.