Typi—case study

Web typography is complicated. We, as designers and developers, need to design/build for a fluid canvas that change depending on what a user uses to interact with our sites. For many years, we have looked into web typography’s predecessor – print typography – to find hints on what good web typography should be.

Unfortunately, many typography enthusiasts tried to impose print typography principles that were impractical for the web era – they required too much code, code that’s unmaintainable for a reasonably-sized website. Some don’t think enough, believing it’s alright to imprint whatever traditions we have in print typography directly into web typography. Some even go to a point to claim that web typography is broken.

As a beginner to typography then, I found tonnes of information about print theories and how people claim it should be applied to the web, but I wasn’t able to find anyone who applies these theories in a way that’s easy to code, and easy to change – which my definition of maintainable.

So, I set out to research typography. Typi is the result from a few months of research on both typography principles and the integration of relevant principles into code.

In this case study, you’ll hear about why Typi is designed the way it is and how I created it.

Designing the Typi API

The design process began by understanding print typography principles, figuring out which ones are important for web typography and why they matter. This meant I had to find an answer for the big question – what is good typography?

Good typography is typography that lets one read without distractions. Good typography, at the basic level, is invisible to the user as they read through the text on a page. Great typography is able to depict the emotions and captivate the reader while they read.

To create great typography, you need to know how typefaces evoke different emotions. It was something way out of my reach when I began the research; so, I focused my energies on creating good typography instead. This research led me to discover that typesetting – the process to setting font-size, leading and measure – is the most important part of typography.

Typi focuses directly on typesetting. I believe the key to maintainable typography is to allow designers and developers to change the font-size and line-height (what we use to determine leading on the web) of any text element easily. The measure (width of text) can be constrained with layouts, so that’s not too much of a problem.

The Typi API

Typi relies on Sass – a CSS preprocessor language that’s incredibly prolific at the time I wrote the library. It uses Sass maps, which contains key-value pairs. Each key gives meaning to the value it holds, and it allows users to easily understand what’s going on.

At the bare minimum, Typi looks like this:

$typi: ( base: ( null: ( 16px, 1.4, ), ),);The key, base, indicates that you’re creating a sass map for the base font-size and line-height values you’d use for your body text.

The key, null, tells Typi to create the font-size and line-height values without media queries (which is often needed for responsive websites).

The first number, 16px, is the font-size to create at the null breakpoint.

The second number, 1.4, is the line-height value to use at the null breakpoint.

Accessible typography

Good typography is also accessible typography – readers should be able to read without squinting their eyes.

Since we use multiple devices to view sites, and we usually place larger devices further away from our eyes, we need to increase the base font-size for larger devices. This process is often done with media queries, like this:

html { font-size: 16px; line-height: 1.4;}

@media screen and (min-width: 600px) { html { font-size: 18px; }}

@media screen and (min-width: 800px) { html { font-size: 19px; line-height: 1.45; }}

@media screen and (min-width: 1200px) { html { font-size: 21px; }}As you can see, the process is a downright chore, which is why many developers hate media queries when working with typography.

With Typi, the process can be completed with a few key-value pairs, like the ones you’ll see below. If you see only a single font-size value, that means Typi should not write a line-height value, but instead allow CSS to cascade downwards.

// Typi map holds font configurations$typi: ( base: ( null: ( 16px, 1.4, ) medium: ( 18px, ), large: ( 19px, 1.45, ), huge: ( 21px, ), ),);The keys (medium, large and huge) are media query breakpoints that must be predetermined with another Sass map – the $breakpoints map:

// Creating breakpoints for media queries$breakpoints: ( medium: 600px, large: 800px, huge: 1200px,);Now, switching font-sizes and line-heights across breakpoints become easy – you simply change a value in your $typi map.

Another point about accessible typefaces is this – as developers, we want to accommodate users with not-so-good eyesight. These users may opt to increase the browser font-size from the default 16px to 20px. To accommadate these users, we have to use relative units (like em and rem) whenever we write font-size values for typographic elements. Typi does this conversion for you automatically.

More information about using Typi can be found in its Github repo.

Contrast and Rhythm

Music is beautiful. It flows. We enjoy it. The reason we enjoy music is because it follows a rhythm. Likewise, good typography allows a reader to flow through the text when it follows a rhythm. On the web, we often call this rhythm vertical rhythm.

Vertical rhythm is the downwards motion of text. It’s the amount of space between each line, between each paragraph, and between any two elements on the page. This rhythm needs to be consistent enough to induce a flow. For that, the greatest repeating number – the line height of the body text – creates the rhythm that the rest of the page flows with. To understand more about vertical rhythm, you might want to read “what is vertical rhythm”.

Typi provides a rhythm function that allows you to calculate and use the line height value (the most commonly repeated value) easily. Here’s a quick example:

$typi: ( base: ( null: ( 16px, 1.4, ), ),);

// The line-height value is 16px * 1.4 = 22.4.x.selector { // This means 4 * 22.4px, but in written in rem for accessibility and maintainability purposes margin-top: vr(4);}For more information about Typi’s rhythm function, be sure to check out the Typi’s Github repo.

Now, music would be boring if you listen to a note with same beat, pitch, and texture on repeat. It’ll be similar to listening to a monk knock a wooden fish without the chanting the sutras – it’s boring.

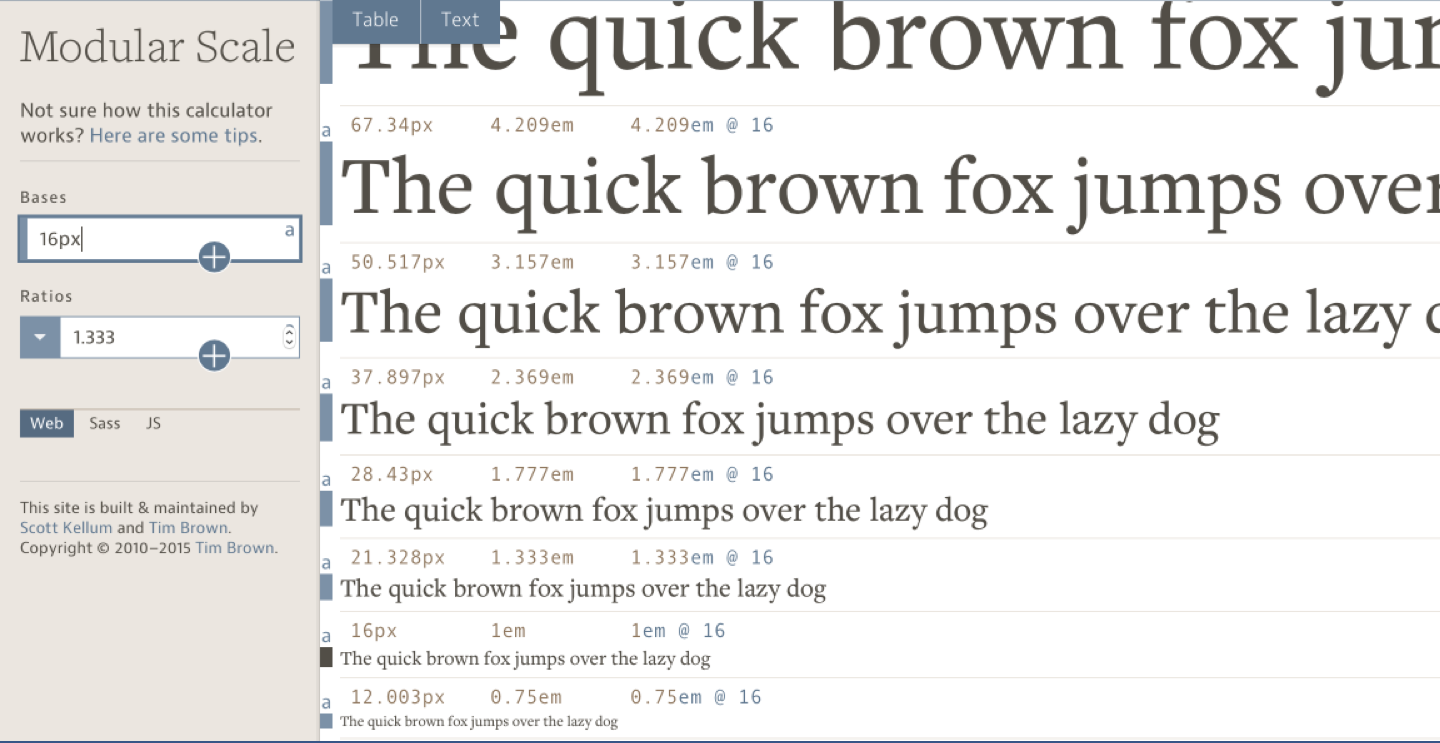

Music is beautiful because there’s contrast. The contrast – the difference between high and the lows – catch our attention and allows us to differentiate one part of the music from another. In typography, we also need contrast, and we often create contrast between headings and text font-sizes through a technique called Modular Scale. For more information, you might want to read “More Meaningful Typography” by Tim Brown.

To make it easy to code, Typi lets you to use Modular Scale Sass library directly in the $typi map. You simply have to substitute the font-size with a modular scale function, like this:

$typi: ( base: ( null: ( 16px, 1.4, ), ), h1: ( null: ms(3), ),);A course on typography

What else goes into good typography?

Other than the things I mentioned in this case study, nothing much. What’s important is to learn to typeset, internalize the process, understand why typesetting is important, and how the principles of design (repetition, contrast, alignment and proximity) play in typography. Once you understand these, web typography becomes a fun playground for you instead of a stress-filled zone. (Oh, of course, you need to be able to translate these principles to the web!).

For me, learning about web typography and creating scalable typography was a lot of fun, but also a lot of frustration. I summarized my findings and learnings (both design and code) into a course – Mastering Responsive Typography – that would help you learn everything I know today.

If you’re interested, you can get the first four lessons of Mastering Responsive Typography for free through the link below. I invite you to check it out.

Get the first four lessons of Mastering Responsive Typography for free.

Wrapping up

Creating Typi was a tough process. It taught me how to research about a touchy topic that people have different opinions on. It taught me to understand best practices from the founding principles so I know how to use them properly. It also taught me how to design a clean API that focuses on the principles while integrating existing approaches in the market.

Creating the library itself also taught me the ins-and-outs of writing a library in Sass. The process and functions used are totally different from how you might do it with JavaScript. I’m glad I made Typi, and I’m glad to hear how many people are using it to help with their development efforts.

Once again, if you’re curious about Typi, you can check out the Github repo. Admittedly, I should also have created a microsite to explain the benefits of Typi, but I’ve since moved past that and I’m focusing on something else now. I hope you find Typi useful! (And please let me know if you ever want to contribute to Typi!).

If you’re interested to hire me to help you design and simplify an existing workflow within your company (like creating Typi, using Webpack, or any other possible variations), I’d love to chat! The idea is you feel that something can be done better, and should be done better. If you feel this way, please feel free to tell me more about your project and how I can help you over at the application page.

(Note: I’m currently accepting project requests for April – Jun, 2018. I can only take up to 2 clients during this period, so please apply now if you’re interested to work together with me!)