How to Modularize HTML Using Template Engines and Gulp

Template Engines are tools that help us break HTML code into smaller pieces that we can reuse across multiple HTML files. They also give you the power to feed data into variables that help you simplify your code.

You can only use template engines if you had a way to compile them into HTML. This means that you can only use them if you’re working with a backend language, or if you’re using client-side JavaScript.

However, with Node.js, we can now harness the power of template engines easily through the use of tools like Gulp.

That’s what we’re going to cover today in this chapter. We’re going to find out what template engines are, why we should use them, and how to set one up with Gulp.

Let’s start by looking more closely at the two main benefits that template engines bring.

Two benefits of template engines

Here are the two benefits that template engines bring:

- It lets you break HTML code into smaller files

- It lets you use data to populate your markup

Let’s go through them one by one.

Breaking HTML into smaller files

It’s common for a HTML file to contain blocks of code that are repeated across the website. Consider this markup for a second:

<body> <nav>...</nav> <div class="content">...</div> <footer>...</footer></body>Much of these code, particularly those within nav and footer, are repeated across multiple pages.

Since they are repeated, we can pull them out and place them into smaller files called partials.

For example, the navigation partial may contain a simple navigation like this:

<!-- Navigation Partial --><nav> <a href="index.html">Home</a> <a href="about.html">About</a> <a href="contact.html">Contact</a></nav>Then, we can reuse this partial across our HTML files. Here’s what HTML files might look like with partials included:

<body> {% include partials "nav" %} <div class="content">...</div> {% include partials "footer" %}</body>Note: The syntax for including partials are different for each template engine. This one shown above is for Nunjucks or Swig.

There’s one great thing about being able to break code up like this.

Just imagine what you would do if you had to change the navigation now. When you use a partial, all you have to do is change code in the navigation partial and all your pages will be updated. Contrast that with having to change the same code across every file the navigation is used on. Which is easier and more effective?

This ability to break code up into smaller files helps us write lesser (duplicated) code while at the same time preserve our sanity when code need to be changed.

Let’s move on to the second benefit.

Using data to populate markup

This benefit is best explained with an example. Let’s say you’re creating a gallery of images. Your markup would be something similar to this:

<div class="gallery"> <div class="gallery__item"> <img src="item-1.png" alt="item-1" /> </div> <div class="gallery__item"> <img src="item-2.png" alt="item-2" /> </div> <div class="gallery__item"> <img src="item-3.png" alt="item-3" /> </div> <div class="gallery__item"> <img src="item-4.png" alt="item-4" /> </div> <div class="gallery__item"> <img src="item-5.png" alt="item-5" /> </div></div>Notice how the .gallery__item div was repeated multiple times above?

If you had to change the markup of one .gallery__item, you’d have to change it in five different places.

Now, imagine if you had the ability to write HTML with some sort of logic. You’d probably write something similar to this:

<div class="gallery"> // Some code to loop through the following 5 times: <div class="gallery__item"> <img src="$path-to-image" alt="$alt-text" /> </div> // end loop</div>Template engines gives you the ability to use such a loop. Instead of looping exactly five times, it loops through a set of data that you pass to it. The html would become:

<div class="gallery"> {% for image in images %} <div class="gallery__item"> <img src="{{src}}" alt="{{alt}}" /> </div> {% endfor %}</div>The data would be a JSON file that resembles the following:

{ "images": [ { "src": "item1.png", "alt": "alt text for item1" }, { "src": "item2.png", "alt": "alt text for item1" } // ... Until the end of your data ]}When the data is supplied, the template engine would create a markup such that the number of .gallery__items would correspond to the number of items in the images array of the data.

The best part is that you only have to change the markup once and all .gallery__items would be updated.

Here, template engines once again gives you the ability to write lesser code, and helps preserve your sanity when code needs to be changed.

Since we know what template engines does now, lets move on and learn how use a template engine with Gulp.

Using a template engine with Gulp

Before we move on and create a gulp task that uses a template engine, let’s look at a list of popular template engines that Gulp is able to use (Note: They’re all JavaScript based templat engines).

Here’s the list in alphabetical order:

- Dust.js

- Embedded JS (ejs)

- Handlebars

- Hogan.js

- Jade

- Mustache

- Nunjucks

- Swig (Note: no longer maintained)

Each template engine is unique. It has it’s pros and cons and it’s syntax can be wildly different from other template engines. Because of this, let’s learn to use one template engine in this article – Nunjucks.

You can opt to use other template engines if you wish to, but the instructions to use them will be different.

I highly recommend Nunjucks because it’s extremely powerful. It has features (like inheritance) that most template engines do not have. I’ve also used Mustache and Handlebars previously, and found that they weren’t powerful enough in many circumstances.

Now, let’s implement Nunjucks into our workflow.

Using Nunjucks with Gulp

We can use Nunjucks through a plugin called gulp-nunjucks-render

Let’s start by installing gulp-nunjucks-render.

npm install gulp-nunjucks-render --save-devvar nunjucksRender = require('gulp-nunjucks-render')Next, we need to create a project structure that allows us to use Nunjucks easily. We will use this structure:

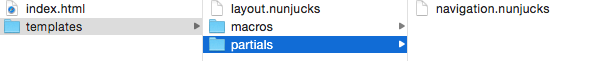

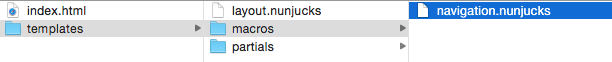

project/ |- app/ |- index.html and other .html files |- pages/ |- templates/ |- partials/The templates folder is used for storing all Nunjucks partials and other Nunjucks files that will be added to files in the pages folder.

The pages folder is used for storing files that will be compiled into HTML. Once they are compiled, they will be created in the app folder.

Let’s work through the process of creating some Nunjucks files before creating the Gulp task.

First of all, one good thing about Nunjucks (that other template engines might not have) is that it allows you to create a template that contains boilerplate HTMl code which can be inherited by other pages. Let’s call this boilerplate HTML layout.nunjucks.

Create a file called layout.nunjucks and place it in your templates folder. It should contain some boilerplate code like <html>, <head> and <body> tags. It can also contain things that are similar across all your pages, like links to CSS and JavaScript files.

Here’s an example of a layout.nunjucks file:

<!-- layout.nunjucks --><!DOCTYPE html><html lang="en"> <head> <meta charset="UTF-8" /> <title>Document</title> <link rel="stylesheet" href="css/styles.css" /> </head> <body> <!-- You write code for this content block in another file --> {% block content %} {% endblock %}

<script src="bower_components/jquery/dist/jquery.js"></script> <script src="js/main.js"></script> </body></html>By the way, I prefer to use the .nunjucks extension for Nunjucks files and partials because it lets me know that I’m working with Nunjucks. If you’re not comfortable with .nunjucks, feel free to leave your files as .html.

Edit: You can use.njk now. It has became the standard.

Next, let’s create a index.nunjucks file in the pages directory. This file would eventually be converted into index.html and placed in the app folder.

It should extend layouts.nunjucks so it contains the boilerplate code we defined in layout.nunjucks:

<!-- index.nunjucks -->{% extends "layout.nunjucks" %}We can then add HTML code that’s specific to index.nunjucks between {% block content %} and {% endblock %}.

<!-- index.nunjucks -->{% extends "layout.nunjucks" %} {% block content %}<h1>This is the index page</h1>{% endblock %}We’re done with setting up Nunjucks files. Now, let’s create a nunjucks task that coverts index.nunjucks into index.html.

gulp.task('nunjucks', function () { // nunjucks stuff here})The nunjucks-render allows us to specify a path to the templates with the path option:

gulp.task('nunjucks', function () { // Gets .html and .nunjucks files in pages return ( gulp .src('app/pages/**/*.+(html|nunjucks)') // Renders template with nunjucks .pipe( nunjucksRender({ path: ['app/templates'], }) ) // output files in app folder .pipe(gulp.dest('app')) )})Now, try running gulp nunjucks in your command line. Gulp would have created an index.html and placed it in the app folder for you.

If you opened up this index.html file, you should see the following code:

<!DOCTYPE html><html lang="en"> <head> <meta charset="UTF-8" /> <title>Document</title> <link rel="stylesheet" href="css/styles.css" /> </head>

<body> <h1>This is the index page</h1> <script src="js/main.js"></script> </body></html>Notice how everything (except the <h1> tag) came from layouts.nunjucks? That’s what layout.nunjucks is for. If you need to mess around with the <head> tag, add JavaScript or change CSS files, you know you can do it in layouts.nunjucks and every single page will be updated accordingly.

At this point, you’ve successfully extended layouts.nunjucks into index.nunjucks and rendered it index.nunjucks into index.html. There’s a few more things we can improve on. One of the things we can do is to learn to use a partial.

Adding a Nunjucks Partial

We need to create a partial before we can add it to index.nunjucks. Let’s create a partial called navigation.nunjucks and place it in a partials folder that’s within the templates folder.

Then, let’s add a simple navigation to this partial:

<!-- navigation.nunjucks --><nav> <a href="#">Home</a> <a href="#">About</a> <a href="#">Contact</a></nav>Let’s now add the partial to our index.nunjucks file. We can add partials with the help of the {% include "path-to-partial" %} statement that Nunjucks provides.

{% block content %}

<h1>This is the index page</h1><!-- Adds the navigation partial -->{% include "partials/navigation.nunjucks" %} {% endblock %}Now, if you run gulp nunjucks, you should get a index.html file with the following code:

<!-- <head> and CSS -->

<h1>This is the index page</h1>

<nav> <a href="#">Home</a> <a href="#">About</a> <a href="#">Contact</a></nav>

<!-- JavaScript and </body> -->That wasn’t so hard, was it? :)

Let’s move on. When using partials like navigation, we can often run into situations where we had to add a class to one of the links when we’re on the page. Here’s an example:

<nav> <!-- active class should only on be present on the homepage --> <a href="#" class="active">Home</a> <a href="#">About</a> <a href="#">Contact</a></nav>The active class should only be present on the homepage link if we’re on the homepage. If we’re on the about page, then the active class should only be present on the about link.

We can do this with a slightly modified version of partials called Macros. The only difference is that you can add variables to it just like working with a function in JavaScript

Now, let’s learn to use a macro as the navigation instead.

Adding a Nunjucks Macro

First, let’s create a nav-macro.nunjucks file in a macros folder that is within the templates folder. (We’re using nav-macro to make sure you don’t get confused between the two navigation nunjuck files)

We can begin writing macros once you have created the nav-macro.nunjucks file. All macros begin and end with the following tags:

{% macro functionName() %}<!-- Macro stuff here -->{% endmacro %}Let’s create a macro called active. It’s purpose is to output the active class for the navigation. It should take one argument, activePage, that defaults to 'home'.

{% macro active(activePage='home') %}<!-- Macro stuff here -->{% endmacro %}We’ll write HTML that would be created within the macro. Here, we can also use the if function provided by Nunjucks to check if an active class should be added:

{% macro active(activePage='home') %}<nav> <a href="#" class="{%if activePage == 'home' %} active {% endif %}">Home</a> <!-- Repeat for about and contact --></nav>{% endmacro %}We’re done writing the macro now. Let’s learn to use it in index.nunjucks next.

We use the import function in Nunjucks to add a macro file. (We used an include function when we added a partial previously). When we import a macro file, we have to set it as a variable as well. Here’s an example:

<!-- index.nunjucks -->{% block content %}

<!-- Importing Nunjucks Macro -->{% import 'macros/nav-macro.nunjucks' as nav %} {% endblock %}In this case, we’ve set the nav variable as the entire nav-macro.nunjucks macro file. We can then use the nav variable to call any macro that were written in the file.

{% import 'macros/nav-macro.nunjucks' as nav %}<!-- Creating the navigation with activePage = 'home' -->{{nav.active('home')}}With this change, try running gulp nunjucks again and you should be able to see this output:

<nav> <a href="#" class=" active ">Home</a> <a href="#" class="">About</a> <a href="#" class="">Contact</a></nav>That’s it for using Macros. Knowing this would invariably help you out a lot while using Nunjucks :)

There’s one more thing we can do to enhance our templating experience with Nunjucks, and that’s populating the HTML with data.

Populating HTML with data

Let’s start by creating a file called data.json that contains your data. I’d recommend you place this data.json in the app folder.

$ cd app$ touch data.jsonLet’s add some data now. We can use the data from the earlier example.

{ "images": [{ "src": "image-one.png", "alt": "Image one alt text" }, { "src": "image-two.png", "alt": "Image two alt text" }]}We then have to tweak the nunjucks task slightly to use data from this data.json file. To do so, we need to use to the help of another gulp plugin called gulp-data.

Let’s install gulp-data before moving on.

$ npm install gulp-data --save-devvar data = require('gulp-data')Gulp-data takes in a function that allows you to return a file. We can use the require function Node provides to get this data file:

.pipe(data(function() { return require('./app/data.json')}))When using require to get files from a custom directory (not node_modules), we need to tell Node the path to the directory. Here, we start with a ./ that tells Node to start with the current directory, then look into app for the data.json file.

Note: A better way is to use two functions, JSON.parse() and fs.readFileSync() instead of require. We will cover how to do so in “Automating Your Workflow with Gulp”.

Let’s add the gulp-data to our nunjucks task now.

gulp.task('nunjucks', function () { return ( gulp .src('app/pages/**/*.+(html|nunjucks)') // Adding data to Nunjucks .pipe( data(function () { return require('./app/data.json') }) ) .pipe( nunjucksRender({ path: ['app/templates'], }) ) .pipe(gulp.dest('app')) )})Finally, let’s add some markup to index.nunjucks so it uses the data we’ve added.

<!-- index.nunjucks -->{% block content %}<div class="gallery"> <!-- Loops through "images" array --> {% for image in images %} <div class="gallery__item"> <img src="{{image.src}}" alt="{{image.alt}}" /> </div> {% endfor %}</div>{% endblock %}<div class="gallery"> <div class="gallery__item"> <img src="image-one.png" alt="Image one alt text" /> </div> Now, if you run `gulp nunjucks`, you should get a `index.html` file with the following markup:

<div class="gallery__item"> <img src="image-two.png" alt="Image two alt text" /> </div></div>Nice!

That’s the basics to using the Nunjucks template engine with Gulp. Let’s wrap this article up now.

Wrapping up

We’ve learned how template engines make development much easier and how to use them in general.

In this chapter we’ve learned how template engines make development much easier, and how to use them (in a general sense).

We then dove deeper into one template engine, Nunjucks, got it to work with Gulp, and learned how to use three Nunjucks provides:

extendto inherit a Nunjucks fileincludeto include a partialimportto import a macro

FYI, the information we covered here is just half of one chapter in Automating Your Workflow :)

The rest of this chapter are about three things that I’m unable to cover in this article since it requires information from earlier parts of the book. They are:

- Watching and compiling nunjucks files

- Preventing errors from Nunjucks from breaking Gulp’s watch

- Reloading the browser automatically whenever a file changes

These three things help speed your entire workflow up, so it can be super beneficial for you if you manage to integrate them into your workflow.

Check out Automating Your Workflow if you’re curious to learn how to do so.

What did you think of this article? I’d love to hear your questions and comments so please leave them below.