Migrating to a new Mac

Setting up a new Mac is painful. Here are some of the things I have to do:

- Install all 47 applications I use every day.

- Provide the right credentials for each application.

- Change macOS default settings to the ones I like.

- Set up coding configurations.

- Move files from the old Mac to the new one.

I estimate at least a three day’s worth of work (downloading things and waiting for them to download 😴) if I have to install everything manually.

But I was able to set my computer up in hours (automatically) thanks to dotfiles.

What are dotfiles?

Dotfiles is a collective name for all files that begin with a dot. Examples include:

.eslintrc.gitignore.editorconfig

To the programming community, dotfiles are more than a name for files that begin with a dot. They refer to startup scripts that help you set up new computers.

(I have no idea why programmers call startup scripts dotfiles. Maybe because dotfiles sound sexier? ¯_(ツ)_/¯).

For clarity purposes, I’ll use these terms:

- Dotfiles: files that begin with

.. - Startup scripts: scripts that help set up the computer.

What dotfiles do

A dotfile is used to configure how applications behave. For example:

.gitconfigand.gitignorechanges howgitbehaves..eslintrcchanges how ES Lint behaves..editorconfigchanges how many text editors behave.

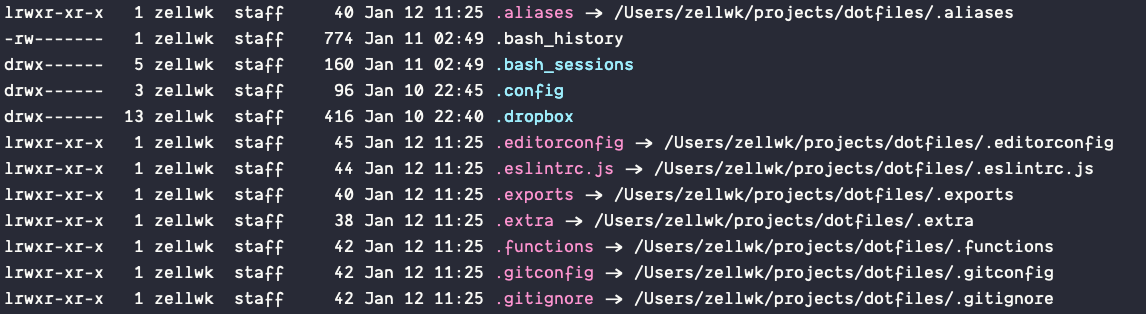

These files live on your computer’s $HOME directory. If you want to see what dotfiles you have, simply open up your Terminal app and type ls -la. You’ll see a list of dotfiles.

Here’s what mine looks like now:

Note: It’s okay if you don’t know what dotfiles are. They’re not important for this article. I just had to explain the difference between dotfiles and startup scripts 😉.

What’s more interesting is the next part: Startup scripts.

My Startup script

If you get a new computer, you can run a startup script to:

- Download applications

- Change default settings

My startup script (aptly named: Dotfiles ¯\_(ツ)_/¯) helps me install 31 out of the 47 applications I use. This saves me a huge ton of work!

It also helps me install commands that I use regularly on my command line. Examples include: svgo and http-server. (Note: These “commands” are generally called command line interfaces, or CLIs).

The startup script does it through three files:

Brew.shnpm.sh.macos

Brew.sh

Brew is a shorthand for Homebrew. Homebrew lets you download packages onto macOS or Linux computers through the command line.

It can help you install useful things like:

- Node

- PHP

- Git

- Openssh

It can also help you install applications. Here’s a list of 31 applications I install with Homebrew.

- 1password

- Alfred

- Beamer

- Dash

- Dropbox

- Firefox

- Firefox Nightly

- Chrome

- Chrome Canary

- Grammarly

- Iterm2

- Kap

- Marked

- Messenger

- MongoDB Compass

- Moom

- Mplayerx

- Notion

- Obs

- Odrive

- Postman

- Sketch

- Skitch

- Skype

- Slack

- Spotify

- Telegram

- Textexpander

- Tower

- Visual Studio Code

npm.sh

npm lets you download JavaScript packages onto your computer. Many frontend development toolchains rely on npm. It comes installed with Node, and I installed Node with Brew.

After running brew.sh, I configured my npm and install additional CLIs I use frequently. These include http-server and svgo that I mentioned above.

.macos

.macos helps you set up a new Mac with sensible default settings.

Here, I copied Mathias Bynens .macos script and modified it to my personal preferences. You may want to refer to his version if you intend to build your own .macos file.

Symlinked dotfiles

(Note: This is an advanced section for people who use dotfiles).

Earlier, I mentioned that dotfiles can be found in the $HOME folder. (Every Terminal app opens the $HOME folder by default).

If you want to see what dotfiles you have, you can open your Terminal app and type ls -la. You’ll see a list of dotfiles.

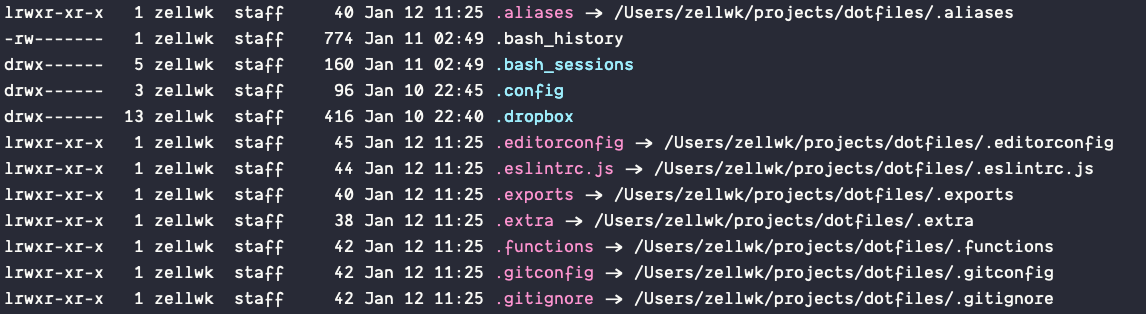

I also showed you what mine looks like:

Notice the dotfiles in pink? These dotfiles also have a -> to another file. The -> indicates the dotfile in the $HOME folder is symlinked to the dotfile in my dotfiles project.

What is a symlink?

Symlink means symbolic link. It lets you open a file from a second location.

Here’s how it works:

- You decide on a source file

- You choose a second location (a destination) to open the file with.

- You run the symlink command.

- Once you run the symlink command, this destination file will point to the source file.

In the case above, if I open .gitconfig from $HOME, I’m actually opening .gitconfig from /Users/zellwk/project/dotfiles.

Why create a symlink?

Dotfiles can change. I want to make sure my Dotfiles repo is updated with the latest changes.

If I don’t create symlinks, I’ll forget to update my dotfiles project. (This has happened before with the dotfiles on my old computer 🤭).

I created a link.sh file in the Dotfiles repo to help with creating symlinks. If I ever create a new dotfile in my Dotfiles repo, I just have to run link.sh to make sure everything is synced up properly 🤓.

Finally, let’s talk about the most important part: setting up my code editor.

Setting up my code editor

I’m anal when it comes things I use. Particularly things I use on a daily basis. I had to make sure my text editor is perfect to my own likings (and I spent days to configuring it… I don’t want to do it again…).

I use Visual Studio Code (VSCode from now on) as my text editor. It has a plugin that lets you sync everything you’ve configured onto another computer. The plugin is called Settings Sync.

Here’s how to set it up:

First, create a personal Github OAuth Token according to the instructions on Settings Sync.

On the old computer:

- Run the

Sync: Update / Upload Settingscommand in VSCode. - It’ll ask for authentication.

- Insert the OAuth Token you created into the box provided.

- Hit enter.

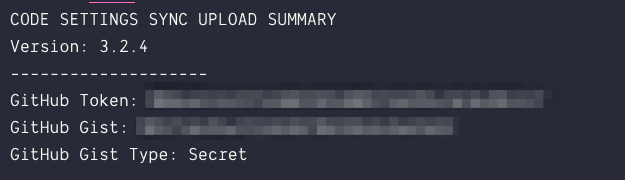

Wait for ~10 seconds for the plugin to sync your settings into a Github Gist. Once it’s done, you’ll see the VS Code integrated shell. Scroll up and you’ll see the OAuth token you used and the Gist ID the plugin stored your settings.

SAVE THESE SOMEWHERE. YOU WILL NEVER SEE THEM AGAIN.

(No need to panic if you’ve lost them. Do the syncing process ☝️ again and you’ll get new keys).

On the new computer:

- Run the

Sync: Download settingsin VSCode - Fill in your Github OAuth token

- Fill in your Gist ID

Settings Sync will do its job and sync everything you’ve configured in VS Code. (Yes, this includes extensions too!).

Wrapping up

That’s everything I could automate as I transitioned from my old Mac to the new one. I hope you found/learned something useful in this series!

Other articles in this series:

- Setting up my new Mac (Part 1—the apps I use)

- This article